Here is an Op Ed piece that I did which appeared in The Hill this morning in support of the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement. I welcome your comments.

Crenshaw Consulting Associates

Business Advice with Integrity

Here is an Op Ed piece that I did which appeared in The Hill this morning in support of the Trans Pacific Partnership (TPP) trade agreement. I welcome your comments.

So I have raised the hackles of my esteemed Warthog (A-10) brothers and sisters and Army and Marine

ground pounders before in an article entitled “The A-10 and Reality.” In that article I took the position that the A-10, even though it was a good airplane for its time (first flown in 1972), should be retired. I still believe that its time has come. You can read the details by going to the link, but my opinion is still that while it would be nice to have if the Air Force had unlimited amounts of money, it doesn’t. The A-10 is expensive to fly and maintain, it takes lots of logistics and people support and I question its survivability at low altitudes, given the proliferation and availability of hand-held SAMs. As I recall, there are usually altitude restrictions put into place in most combat situations to keep the aircraft out of threat envelopes, and I would submit these restrictions negate many of the advantages of an A-10 in a close air support role (CAS).

So why am I messing with this still festering wound? I just read about the impending (if you can define 3 years as impending)fly-off between the JSF and the A-10 to see which jet will win the CAS Crown. It’s been amusing to sit on the sidelines and see how this fandango developed. First, the Pentagon’s Test and Evaluation gurus, bowing to the extreme pressure from the Hill to keep the A-10, announced that sometime in 2017 or 2018 they would evaluate the JSF’s ability to be an effective CAS platform…Don’t you think it’s a little late to be thinking about that? I am just stunned that we would get this far without already knowing the answer to that question. Never mind that no matter what the outcome, we will still buy all the JSFs our increasingly limited defense dollars will buy (to the detriment of all other weapons systems, I might add). And because of all the other pressures, we will most likely have to retire the A-10 anyway. And this will be even more true three years from now when we finally get around to doing the tests.

Given all the problems we have in DoD acquisition, I think we could be putting our limited dollars and unlimited talents towards just getting the JSF delivered with some sort of combat capability, or figure out how to recapitalize the nuclear deterrence force, or figure out how to prevent some rag-tag bunch of cyber terrorists from obtaining every bit of personal/private information that I put on my security clearance application. Or figuring out how to actually win the PR war against ISIS…After all, isn’t this the land of Mad Men, Cyber-superiority and endless imagination? I just can’t figure out how those ISIS characters continue to scoop the US in the world of social media. A cynic might think we should hire ISIS to do the recruiting ads for us…(that’s just a joke for you NSA guys monitoring my web site!!)

The point is it is stunning to me that we have only decided to look at JSF CAS capabilities decades into its development and well past the point of no return. We will spend Tens of Millions of dollars to find out the answer to a question to which we already know the answer. I guess that I’m not surprised since given the copious quality of cash flowing through the JSF coffers, a few Tens of Millions of dollars probably don’t even break the event horizon.

But I digress….To continue the JSF/A-10 CAS saga, after the OSD poobahs announced the “fly-off”, Air Force Chief of Staff, General Mark Welsh says, “I think is would be a silly exercise.” YA THINK???? Of course, after he made those remarks, I’m sure he had a little one-on-one counseling over at the Pentagon. Hence, a few days later it was announced that the Air Force leadership is “fully on-board with the planned test schedule.” Sigh, you can’t make this stuff up!

I guess you are wondering which jet I think will win. The Warthog, of course. The A-10 was designed with a single purpose in mind…CAS. You know what? my guess is that if they did a fly-off between the JSF and the A-6 Intruder for gunsight bombing, the A-6 would reign supreme!

This whole episode reminds me of a quote by Emerson,”A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds, adored by little statesmen and philosophers and divines.” I’m all for protecting our brave troops on the ground,but I think that there will be plenty of 21st Century weapons system available to do that without the A-10.

I guess it’s that time of year when one must talk about all things budget. And since I am only a small gnu within the herd, I too will opine on the obvious. Several thoughts came to mind as I was reading some of the commentary on the budget. It’s always fun to read the DoD press releases and to see the latest spin. How well-educated and experienced people can say some of this stuff with a straight face is a mystery to me. Take the DoD article on its press site today, “Budget Request Balances Today’s Needs Against Tomorrow’s Threats.” The article is a summary of a press conference held by DoD Comptroller, Mike McCord. I love his characterization of the budget: “although planners were aware of financial constraints, the budget is a strategy-driven construct.” Translation–we ignored the budget caps. As an aside, you all know how I hate the way the Pentagon takes common words and complicates them…like “construct“. Don’t they mean plan? I confess that I used to be as bad as the next Pentagonian in inflating words to add an air of sophistication and deep-thoughtedness to them. The “construct” word stands out in my mind because I used it one day while briefing the Chairman of the House Armed Services Committee, Ike Skelton. He stopped me and asked, “What the heck does that mean…construct’? I replied, ” Well, you know…the product of the assimilation of a multitude of facts and non-facts into a non-coherent stream of pseudo-strategy designed to defend an un-defendable position.” Mr. Skelton replied,” Just say plan. Don’t make it so complicated with strange words.” AMEN…..And after that, I tried to avoid Pentagonisms like the plague.

Once again this budget side-steps many of the large issues, like the runaway Joint Strike Fighter budget and focuses in on the marginal stuff…TRICARE rate hikes, cutting Commissary hours, as well as proposing the impossible…base closure, A-10 retirement and the like.

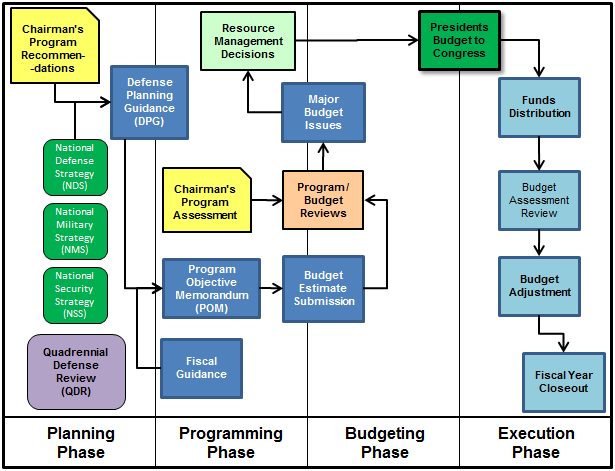

But that’s not the subject of today’s blog, so I will move on from that unpleasantness…….Today’s topic is about HOW the Pentagon arrives at its budget. Of course, it’s fairly common knowledge to this audience that it uses the Planning, Programming Budgeting and Execution (PPBE) system.

A very regimented (or so it used to be) process with a clearly and elegantly articulated set of roles, rules, responsibilities, and schedules. Here is a link to a very well written Army War College paper by LTC Thomas T. Frazier on the history of PPBE system (originally PPBS). Here’s the Cliff Notes version. PPBS was instituted by Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara in the early 60’s because his opinion what that there was no clear process of deciding what to fund and how much to fund. Here is a link to my presentation on how the PPBE system works. Over the last few years the process has morphed from the nice neat process because of Continuing Resolutions, shutdowns, furloughs, war and all manner other issue. Anyway, Secretary McNamara felt that the Pentagon budget process was really one of Incrementalism…just adding more money each year with little thought of where it was going. Interestingly, the things which drove the change came down to six flaws in 1961:

Sound familiar? I submit that all of these factors exist today to some degree or another, perhaps for different reasons than in 1961, but they exist nonetheless. That’s why I think it’s time for a serious discussion about changing the process. Over the past half-century we have fallen back into some very bad habits. They were good reasons for change then, and equally good for change now.

Many would say today’s budgets are very independent of plans. Despite the efforts of the 24,000 or so Pentagon workers, in the end the budgets are determined in large measure by political decisions. I note that the elegant planning process in the Pentagon has recommended decommissioning the A-10, laying up Aegis Cruisers, another round of BRAC, and on and on. These proposals were developed by thousands of planners chewing up millions of man hours, yet the analysis is ignored by the Congress. As the Navy’s N8 I came to the conclusion that at any given moment probably 90% of the people in the Pentagon are working on some part of the budget. But to what ends? At the end of the day, the budget never changes more than about 1% -1.5%, despite the hundreds of thousands of man hours devoted to changing it? Why bother? Given there is so little change, why not stop all the madness of millions of minor budget data base changes which in the end have less than a 1% impact? We could get by with half the people in the Pentagon and let them do something more constructive.

There’s no doubt that we have still to tackle the duplication of effort issue. We still have an unexplainable excess of tactical aircraft in the Air Force, Navy and Marine Corps because no one is willing to give the mission up. Look how much money that one is costing us in the guise of the JSF.

With regard to independent budget development by the Services, that’s still a problem too. How often do you think Air Force budgeteers sit down with the Navy guys to go over their current budget plans…Answer: never…It’s not until OSD gets the budgets that the Services find out what each is really up to. Heck, the Marines don’t share much of their budget with the Navy until end-game, and they are in the same Department!

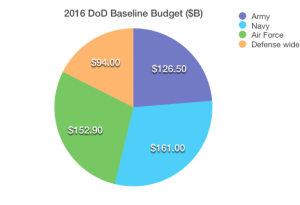

The one-third rule ( every Service is entitled to roughly a third of the DoD budget) is still alive and well in the Pentagon. But because of the growth of the Fourth Estate (DoD agencies and combatant commands according to SECDEF nominee Ash Carter) the pie has been further divided. It’s almost the one-fourth rule now. What’s up with that? The process will never work if one assumes equal shares for all.

As far as budgets being focused on one year, despite the best efforts of DoD to lay in a 5 year plan, it is essentially redone every year. I used to submit the Navy’s 30 Year Shipbuilding plan almost every year with major changes. What kind of long-range plan is that? The truth is that with the way we fight the budget wars from year to year, coupled with the inability of the Congress to regularly and reliably pass funding and authorization legislation, DoD has no choice but to focus on one year. It has become so challenging to execute the budget and build several (the base budget, the sequester budget, the President’s budget, Overseas Contingency Ops budget) that it is impossible to focus on later years.

Perhaps the bright spot is the improvement in the department’s analytical capabilities. We certainly have a world class capability, which produces fantastic analysis. The problem is that it is sometimes ignored by those that matter..either in the Pentagon or on the Hill. To be fair, I should say the analysis is selectively ignored. If the analysis supports your program, it’s cited again and again. If it doesn’t, then one has to play the “experience” or “uncertainty” card. You have all heard that argument: “It’s an uncertain and dangerous world and the analysis does not adequately take that into account. We must rely on our experience and intuition.”

Of course, the PPBE is only one way in which the DoD manages its money. A few years back I gave a presentation on “How DoD Manages Money” in which I cited the following techniques:

It’s too complicated to explain here, but check out the presentation. Even though it was done in 2009, I think it’s relevant today.

So that’s my rail of the day. We need to change the PPBE. I don’t know how. I am not that smart. Maybe some smart combination of the above management systems… I do know that the same reasons we decided to re-twicker the DoD budget process in 1961 exist today. We should convene a group of smart folks (and not just old fogies like me who got us into this mess in the first place) to consider how to develop a process which eliminates the 1961 reasons. It’s time for some new and innovative thinking, done by all interested parties (Congress, DoD, Administration) on how to fix the problem.

Those of you who have read some of my previous musings know that I have a bee in my bonnet about Pentagon “Double Speak.” You know… the overly complicated buzzwords and phrases for simple things. Here’s a link to one of my articles that has some examples. A few of my favorites include:

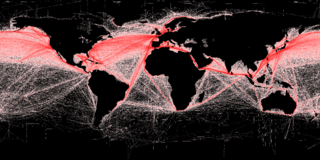

As I was reading the news this morning, I found this article on the name change of the “Air Sea Battle” concept in DoD Buzz. So forget about Air-Sea Battle and let me introduce you to Joint Concept for Access and Maneuver in the Global Commons! True to form, the Joint Staff has managed to take a relatively simple name and complicate it to the point of non understanding. Of course what would a new concept be without its accompanying acronym, JAM-GC? I suppose the pronunciation will be JAM-Jic or something like that. I can here the conversation in the Pentagon Food Court now, “What are you working on now?”….”Oh, I’m now the JAM-Jic lead and believe you me there’s lots of jamming and jickin to be done now that this Air-Sea thing has vaporized.”

So, I was never a fan of the Air-Sea Battle thing. IMHO, it was just a budget ploy by the Air Force ( and a somewhat reluctant Navy) to show relevance in an era where it’s relevance was waning. It’s not the first time the Air Force, after becoming alarmed by increasing dependence on and relevance of naval forces, began to seek ways to move into Navy mission territory. This always puzzled me, because in my mind it’s always be a air-sea-land battle. Especially as the perceived budget pressures have forced all the Services to cut force structure. In any serious and protracted campaign, the Navy needs Air Force tanking and command and control capabilities. And the Air Force relies on the assets from the Navy with little or no support requirements to beef up the Joint Force. It was never clear to me why Air Force and Navy needed to invent a “new concept” for something that has always existed….except for the issue of the Joint Strike Fighter. This $160 Billion over-budget, 7 year-late program is costing the King’s treasure and consuming all other aspects of the budgets of both services. Why not influence operational concepts as well? The story line? Air Force and Navy are inextricably linked by the Air-Sea Battle Concept and we must have the JSF to make it work. To the Hawks on the Hill, this can be a very compelling argument. One wonders what was going through the minds of the Army folks while they watched this little menage a deux develop.

Well, I guess the Army dusted things up enough to cause a name change, albeit no less threatening to their budget. As they say in the Patriot’s locker room, “All’s fair in love and war!” So to appease the Army, it appears we now have a new concept. And the name is a doozy…..Joint Concept for Access and Maneuver in the Global Commons.  Access is there to appease the Air Force and Navy, while Maneuver is there to keep the Army below the horizon of the doctrinal landscape.

Access is there to appease the Air Force and Navy, while Maneuver is there to keep the Army below the horizon of the doctrinal landscape.

I have to comment that the new name doesn’t do much for me…..especially the Global Commons piece. To this dinosaur, Global Commons is just a hoity-toity pretentious way for the Pentagon illuminati to show how deep their thoughts are. What is/are the Global Commons? Here’s what Wikipedia says:

a term typically used to describe international, supranational, and global resource domains in which common-pool resources are found. Global commons include the earth’s shared natural resources, such as the deep oceans, the atmosphere, outer space and the Northern and Southern polar regions, the Antarctic in particular. Cyberspace may also meet the definition of a global commons.

I am assuming that in the context of the Pentagon’s understanding, global commons to us unenlightened means “the places we want to be, that others don’t want us to be.” My suggestion for the name of the concept would be the “Enter, Conquer,Stay, Operate” Concept, ECSO or EkSo. It’s sooooo much nicer than Jam-Jic, Don’t you think?

Anyway, as we face serious and deadly threats from everywhere and everything, Syria, Afghanistan, ISIS/L,Budgets, cyber, meteorites, ebola, global warming, etc., it’s good to know we still have thinkers working on US access and maneuver in the Global Commons.

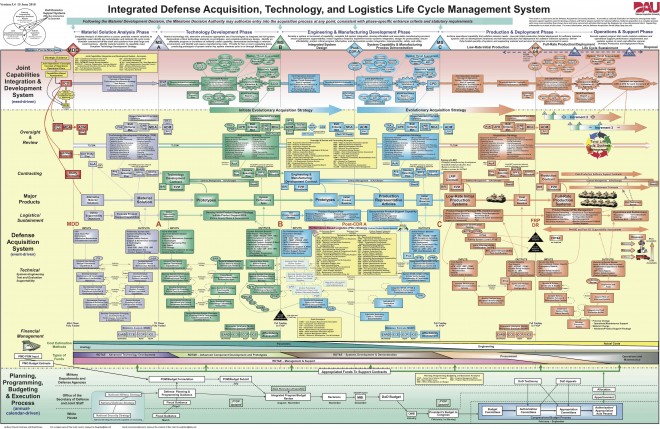

There has been a lot of static on the net lately concerning acquisition reform. Two notable recent arrivals on the scene have been all the buzz around the Beltway: First, the release of Better Buying Power (BBP) 3.0, Under Secretary of Defense (AT&L) Frank Kendall’s reincarnation of BBP 1.0 (originally issued by Ash Carter when AT&L, and later BBP 2.0 by Mr.Kendall).  Second was the publishing of a report by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Chaired by Senator Levin, with Senator McCain as the Ranking Member. The report, entitled “Defense Acquisition Reform: Where Do We Go From Here?, is a collection of essays by 30 experts in the Defense acquisition world about how to improve or reform defense acquisition of things (and to a small degree, services).

Second was the publishing of a report by the Senate Permanent Subcommittee on Investigations, Chaired by Senator Levin, with Senator McCain as the Ranking Member. The report, entitled “Defense Acquisition Reform: Where Do We Go From Here?, is a collection of essays by 30 experts in the Defense acquisition world about how to improve or reform defense acquisition of things (and to a small degree, services).

One of the things I like most about the concept of the Better Buying Series is the iterative process in improving its focus. After letting BBP 1.0 run for a while, corrections were needed as the result of some unintended consequences (like an irrational focus on lowest price, technically acceptable contracts) and need for clarification of some of the elements. BBP 2.0 did just that, directing that more care must be given in defining what is “technically acceptable” for example. Now, BBP 3.0 has come out to further tweak the elements of BBP. A couple of previous elements were eliminated because they were considered complete:

There were some carry overs as well, mostly with refined language. I won’t list them all here, but the ones that I think represent the most significant change are:

Here’s a link to the BBP 3.0 overview. All in all I think it represents a good step forward in the BBP series and will certainly help in trying to understand all the things going on in the world of acquisition reform……..BUT,

Many of the themes that emerged in the second recent arrival, the Senate study (Complete study can be found here) were not really addressed in the BBP 3.0 document. To be fair, the report had yet to be released prior to putting BBP 3.0 on the street, but I would have hoped for more overlap.

The Senate report pulled out four overarching themes from the musings of the 30 experts contributing to the report:

The report also makes two observations which I will quote here:

“First, among all those factors that have been identified as contributing to dysfunction in the defense acquisition system, cultural change is among both the most important and the least amenable to legislation and policy changes. It is, rather, a function of leadership throughout the chain-of-command and an incentive structure that threads through both the government contracting and acquisition workforce and industry that assigns a premium to cost-control and the timely delivery of needed capability.

Second, continued “sequestration” of the DOD’s budgets will undermine any savings that could be achieved through even the most successful acquisition reform.”

Well, to me that says, 1. It’s more of a DoD problem than a legislative problem and 2. sequestration will nullify ( or at least severely impact) all acquisition reform efforts. The last thing we need is even more regulation in the acquisition process. I would offer that in my opinion sequestration is not necessarily the enemy here. I still think we have too much waste in DoD, too many pork barrel projects, too many pet projects and too many cooks in the kitchen. What is the enemy is the uncertainty in the budget process over the last several years….Continuing Resolutions, multiple budgets, Overseas Contingency Funds abuse and a foolish focus on equity in Service budgets have all undermined our ability to reform how we buy things. In the end, it is a indeed a legislative problem….The failure to pass budgets on time, regardless of the funding levels. Life would be so much easier and efficient in DoD acquisition with regular and predictable budgets, passed in a timely fashion and accurately executed.

One final observation: I would like to see the Senate produce a similar document on acquisition reform, but using 30 PRACTITIONERS of acquisition at the grass roots level: Project Managers, PEOs, and Contracting Officers. A view from the top is always useful, but without a view from the bottom we will never really fix what is wrong with acquisition culture. They are the ones that make up the culture, not the poobahs at the top. A little more focus on them would be helpful…I’m not sure that after a contacting officer reads BBP 3.0 they will do anything different.

I saw an interesting article this morning on the NDIA Blog site which said Secretary Frank Kendall, the Under Secretary of Defense for Acquisition, Technology and Logistics USD(AT&L), was unhappy that DoD did not meet the goal for having more competition for defense-related contracts.  I’m not surprised at that because given the irrational focus of DoD on vendor profits, they have managed to make bidding on defense contracts so unattractive that fewer and fewer companies are making the effort to bid. In my view, it’s not just one reason:

I’m not surprised at that because given the irrational focus of DoD on vendor profits, they have managed to make bidding on defense contracts so unattractive that fewer and fewer companies are making the effort to bid. In my view, it’s not just one reason:

I think I will stop at those seven for now, but there are more. What’s fascinating to me is that these reasons are ignored as DoD attempts to develop a fix for limited competition. The DoD solution is to increase regulation, increase reporting frequency (so the bad news comes more quickly I suppose), and continue to monkey around with contractor profits, even on fixed-price contracts. The best way, is to reduce the number of requirements, like those cited above, and let natural instincts and market forces drive competition.

In order to have more bidders, it must become more attractive to bid!

Hello? Did i just say that? Why isn’t the leadership focused on how to make bidding and working on government contracts more attractive? Can it be that simple? I think the answer is yes.

So what does the sewing machine have to do will all of this? This past weekend, the lovely Mrs. Crenshaw volunteered to do a little sewing to get one of our granddaughter’s uniforms ready for school. In order to do this, she needed her sewing machine liberated from the darkest recesses of the attic. I felt like I was in the basement of the Smithsonian as I rummaged throughout the boxes of brass plaques accumulated over the 32 years of my naval career (I’m not allowed to display them). I found a medal I received from the Russians, a box of challenge coins, some old text books from the Naval Academy (why I still have a book on differential equations is beyond me), and various other flotsam and jetsam accumulated over 40+ year of marriage. I finally found the sewing machine, Singer Syle-o-Matic Model 328 (now listed on E Bay as “vintage”). Setting it up after many years of disuse was challenging. It’s a mystery to me why sewing machines work anyway, much like the DoD acquisition process. I started fiddling around with the upper thread tension, adjusting the needle alignment, resetting the timing, changing the motor belt, tweaking the bobbin tension, etc. Before you know it, I had adjusted just about everything on that machine and I had no idea of what the original settings (which worked fine the last time we used it) were. I should have left it alone, done some basic maintenance (a drop of oil perhaps) and let it do its thing. But NOOOOOOOoo! I had to fiddle around with every possible adjustable part and got it so far out of whack that the only option was to go back to basics and take it to a professional. Now it works just fine. I think the same is true in the world of DoD acquisition We have monkeyed around with so many parts that we have lost sight of the original settings—-namely good, old-fashioned competition, unhindered by excessive regulation or government meddling in corporate finances. Why not turn over the management of corporate finances to the professionals (that would be corporate leadership) and let them do what they do best, COMPETE!

So my suggestion on how to increase comptetion is simple: make it more attractive to bid. One does this by eliminating the barriers to bidding, not by adding more.. Take a look at my seven reasons above. If we focused on fixing those, I guarantee you there would be more competition. In the end, the government would get better value for the dollars it spends, not just cheap, mediocre work for which the government is becoming increasingly famous (or infamous, I suppose).

A few weeks ago, Secretary of Defense Hagel published his list of six focus areas for the coming year. Here’s his list:

Really? That’s what he’s focusing on? You probably haven’t heard much about this list because it is sooooo uninspiring. If this isn’t bureaucratic gobbledygook, I don’t know what is. Do you think these are his real priorities, or just the same type of feel-good rhetoric that his staff regularly generates. Ask yourself what the really big issues facing the DoD today are and see if this list scratches the itch. Let’s look at the priorities:

Focus on institutional reform. The subheadings under this priority are reform and reshape our entire defense enterprise, direct more resources to military readiness and capabilities, and make organizations flatter and more responsive. So what are the metrics to use to determine is progress is bring made? As far as I can tell, this focus area should be part of the regular drumbeat of DoD, not some special focus area, implying that we will look at it, fix it and move on. Does he serious think that he is going to reshape the entire defense enterprise? Into what? And does he really mean to direct more resources into readiness, or just cut spending in other areas, only so they can become focus area next year? This one just leaves me uninspired and wondering exactly what we are reforming?

Re-evaluate our military’s force planning construct. This one includes the classic example of Pentagon-speak, namely force planning construct. In the interest of clarity, I believe he means develop a different way to decide how big the Army, Navy, Air Force and Marine Corps needs to be. “Challenge assumptions” is a key part of this focus area. When have you not been to some type of business course where they didn’t say “Challenge the Assumptions?” Exactly what assumptions will we be challenging, who will challenge them and by what process will we evaluate the accuracy and efficacy of the assumptions? In my experience, DoD did a pretty good job translating the National Security Strategy into what wars and other missions we were supposed to be prepared for, turning that into war plans and then figuring out how many forces we needed to execute the plans. The problem was always with the front end in defining what the military would be expected to do. It always turned out to be too expensive. When I first started paying attention to the war fighting expectations I was a policy wonk on the Joint Staff. Back then we were supposed to fight and win two wars simultaneously. That proved so expensive that we had to change it to win one war, while holding our own in another, swinging forces to the the second war once we triumphed in the first. That, too, became too expensive, so we changed to win two wars, but one of them would be the war on terror. Frankly, I’m just not sure what the overarching strategy is these days, but I think it can be found in the 2014 QDR (see QDArghhhhhh). This is what it says: “U.S. forces could defeat a regional adversary in a large-scale multi-phased campaign, and deny the objectives of – or impose unacceptable costs on – another aggressor in another region,” whatever that means.

Prepare for a prolonged military readiness challenge. This is Pentagon-speak for figure out how to do more with less.

Protecting investments in emerging military capabilities. Not sure why this requires the continued focus of SECDEF. Can’t he just say make sure we have enough money in R&D accounts? By the way, here is where the grand plan is not to spend more DoD dollars in R&D, but push off the expense of R&D to industry. That’s not going to work as long as DoD keeps putting pressure on industry to lower profit margins…..Let’s see. I’m a Captain of industry; What’s my priority for where to put the profits I make? 1) Shareholders, 2) capital improvements, 3)cash reserves, 4) corporate jet 5)R&D. Hmmmmm what am I going to cut first when my profits drop????

Achieve balance I guess this is the old “tooth-to-tail” argument that Secretary Rumsfeld was fond of. How much redundancy do we need? How much forcible entry capability do we need? HOw many forces do we station overseas? How many fighters do we need and who gets them? and on and on. We’ve tried this before and the Services resisted any balancing initiatives that left them with less.

Personnel and compensation policy The crux of this priority is to figure out how to have a world-class military force while implementing the lowest price, technically acceptable personnel and compensation schemes. That hasn’t worked so well in the acquisition world and I doubt it will work any better as a personnel policy. This is one I agree that’s needed, but not in its current fashion.

None of these priorities are necessarily bad or wrong, but they are lacking the detail necessary to figure out if they will really make a difference. Is there someone tracking these priorities and providing monthly updates on progress. None of these items are terribly original either. We have all heard these things time and time again. I can remember tackling the issue of balance way back in 1990 with the AC/RC study done by the Joint Staff. I would rather see a list of 5 really vexing issues facing the department and put a concentrated effort into fixing them. The current list has no sense of urgency and just seems like business as usual to me. They are so big, just about everything winds up in a focus area. Why not focus on specific issues?

“OK, Smart guy. What would your priorities be?” you are asking. Here is my list:

I just reread the summary of the 2015 National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) passed by the House on a vote of 385-98. At the end of the day, it appears that the House was not interested in agreeing with many of the cost cutting proposals that DoD had hoped for. Base Realignment and Closure (BRAC) is not an option (see Bric-a-BRAC) , and it looks like the Air Force can keep it’s A-10’s for now. When all is totaled up, the bill accounts for just a shade over $600 Billion in spending. That number is a far cry from what the sequestration number would have been, thanks to the BiPartisan Budget Agreement, but 2016 will be another story.  The Senate also affirmed its desire to keep the A-10s in the inventory in its version of the NDAA.

The Senate also affirmed its desire to keep the A-10s in the inventory in its version of the NDAA.

I happen to agree with the Air Force that it is time for the A-10 to go. It’s expensive to maintain and operate and doesn’t really have a place in the 21st Century battlefield. It pains me to say that, because it was a good airplane for the mission, tank killing and Close Air Support.  My airplane was also the victim of affordability cuts and the entire fleet was scrapped right after it had undergone an expensive and extensive rehabilitation effort. I’m talking about the A-6 Intruder, retired in 1997. No one came to its rescue unlike the A-10. I’m not quite sure why the A-6 retirement didn’t kick up more dust back then except to say that times were tough, money was tight, and everyone recognized the an airplane like the A-6 was vulnerable at low levels against the threat and that with weapons improvements we just didn’t need an airplane that could carry twenty-two 500 pound Mk-82 bombs. What’s the point? With Tomahawks and Joint Stand Off Weapons there was just no need for the A-6. The same is true for the A-10, in my opinion. With today’s technology, the threat environment where the A-10 would be operating would not be survivable. The assumption is that in order to use the A-10, we would have to have Air Supremacy (meaning no enemy airplane flying) and completely neutralized the hand-held SAM threat on the ground. That’s a tall order!

My airplane was also the victim of affordability cuts and the entire fleet was scrapped right after it had undergone an expensive and extensive rehabilitation effort. I’m talking about the A-6 Intruder, retired in 1997. No one came to its rescue unlike the A-10. I’m not quite sure why the A-6 retirement didn’t kick up more dust back then except to say that times were tough, money was tight, and everyone recognized the an airplane like the A-6 was vulnerable at low levels against the threat and that with weapons improvements we just didn’t need an airplane that could carry twenty-two 500 pound Mk-82 bombs. What’s the point? With Tomahawks and Joint Stand Off Weapons there was just no need for the A-6. The same is true for the A-10, in my opinion. With today’s technology, the threat environment where the A-10 would be operating would not be survivable. The assumption is that in order to use the A-10, we would have to have Air Supremacy (meaning no enemy airplane flying) and completely neutralized the hand-held SAM threat on the ground. That’s a tall order!

In today’s world with armed drones…..oooopppps….i meant to say Remotely Piloted Aircraft, there’s just no need to put aircrew at risk. Add to that the expense in maintaining the A-10 and it’s just not worth it……at least not to the Air Force. It IS apparently worth it to members on the Hill who have A-10’s flying in their districts, and the hundreds of airmen required to be in each squadron to maintain the A-10. Sometimes it’s hard to admit you are flying a dinosaur that just doesn’t have a home in the 21st Century.

I just finished plowing through the 2014 Performance of the Defense Acquisition report published by Office of the Under Secretary of Defense, Acquisition, Technology, and Logistics (AT&L).  I was prompted to look at it when I saw this article in the Washington Post on what motivated contractors, according to the report. Pardon my suspicion at a report bragging about how well the current crowd at AT&L is doing, but I’m suspicious. First….there’s a lot of statistics included and my experience is that statisticians can twist the numbers to say anything. As evidence, I note there wasn’t much bad about the JSF (perhaps the worst performing program of all time) in the report. Oh sure, it appears, but if one were to just glance at the charts and graphs where JSF is mentioned, you get the impression that it’s just a middle-of-the pack program…..lots of programs perform worse, a few perform better. EXCUSE ME? This baby is already $160 Billion behind schedule and 10 years late in delivery (and still counting by the way, especially given the disastrous fire at Eglin Air Force Base last week). How DoD can publish a report on performance of the Acquisition system without including a chapter on why the JSF program is so gooned up is beyond me. It’s like the YouTube video when the gorilla walks through the basketball game. Am I the only one who noticed?

I was prompted to look at it when I saw this article in the Washington Post on what motivated contractors, according to the report. Pardon my suspicion at a report bragging about how well the current crowd at AT&L is doing, but I’m suspicious. First….there’s a lot of statistics included and my experience is that statisticians can twist the numbers to say anything. As evidence, I note there wasn’t much bad about the JSF (perhaps the worst performing program of all time) in the report. Oh sure, it appears, but if one were to just glance at the charts and graphs where JSF is mentioned, you get the impression that it’s just a middle-of-the pack program…..lots of programs perform worse, a few perform better. EXCUSE ME? This baby is already $160 Billion behind schedule and 10 years late in delivery (and still counting by the way, especially given the disastrous fire at Eglin Air Force Base last week). How DoD can publish a report on performance of the Acquisition system without including a chapter on why the JSF program is so gooned up is beyond me. It’s like the YouTube video when the gorilla walks through the basketball game. Am I the only one who noticed?

Another item I thought was interesting was the conclusion that although Firm Fixed Price (FFP) contracts do perform better and generally exhibit less cost growth, the report concludes it’s because most of those contracts are lower risk anyway. Oh by the way, the evil part of FFP contracts is that the vendors who do a good job of managing cost and performance of their programs are probably making more profit and therefore gouging the Government. I can hear the conversation in the Pentagon now, “That darn contractor actually delivered on-cost and on-time, so we must have given him too much money!” That substantiates my belief that the Pentagon has the uncanny ability to take from good performing programs to pay for the sins of poor performing programs, thereby dooming all programs to some level of common mediocrity.

One other point I thought was interesting….there’s no mention of contracts that were awarded on a lowest price, technically acceptable (LPTA) basis. Some in industry contend that DoD is so bent on doing things on the cheap, that quality has suffered when contracts are awarded on an LPTA basis. I don’t know if that is just sour grapes from the expensive losers or truth. No one seems to care…….about the quality any way.

Back to the title…..What were the conclusions?

So there you have it. My little list of what incentivizes contractor to perform better goes like this:

To be fair, I think that there have been improvements in the acquisition process and those in the driver’s seat deserve a pat on the back. But in the end, the fundamental problem is that the requirements process never gets it right and we spend lots of time and money recovering. Congress doesn’t help things with its inability to pass a budget either.

I know. I know. You are asking what can this article possibly be about? Well, it’s all about the DoD budget (the Dream) and sequestration (the Nightmare). I’ve been talking to a few budget folks over the past week and asking how is this year compared to others in terms of pain. The universal answer has been “Not so bad this year.” But soon all our dreams of finally getting some sanity in the budget process will give way to the nightmarish and forgotten process known as Sequestration. It’s been quite a journey to get to where the DoD budget is today. Despite all the dire warning about sequestration, all seems to be well for now. There’s some squeaking from the fringes about cuts to force structure, BRAC, pay and benefit cuts, rising health care costs, etc. There are still some struggles going in within the Navy about how many carriers and other combatants the Navy can afford. The Air Force is struggling to make ends meet by removing the A-10 from the battlefield, and the Army and Marine Corps are wrestling with end-strength reductions. Seems like a normal day in DC. I mentioned it’s been quite a journey to get here, and an improbable one at that. Let’s just review the history in case visiting Aliens would like a quick briefing (Do you think they would believe it?) or you want to explain it to your grandchildren.

August 2011. The President signed the Budget Control Act of 2011. The debt ceiling debate was in full swing but the BCA saved the day ( or so we thought). It did a few things:

December 2011. Oooops. The “Super Committee flopped” so the arbitrary cuts demanded by sequestration loomed for next year’s budget.

February 2012. DoD Budget for 2013 ignores sequestration.

December 2012. DoD finally starts planning for possible 2013 spending reductions demanded by sequestration.

January 1, 2013. The American Taxpayer Relief Act of 2012 delays sequestration to March 1, 2013, and cuts some of the sequestration caps.

March 2013. Continuing Resolution funds Government till end of September 2013

October 1-16, 2013. Government Shuts down.

October 16, 2013. Congress passes the Continuing Appropriations Act, 2014 which funded the Government through February 2014 (actually it extended the debt ceiling limit)

December 26, 2013. President signs the Bipartisan Budget Act of 2013 which restored $45 Billion of sequestration cuts in 2014 and $11 Billion in 2015 by adding sequestration cuts to 2022 and 2023.

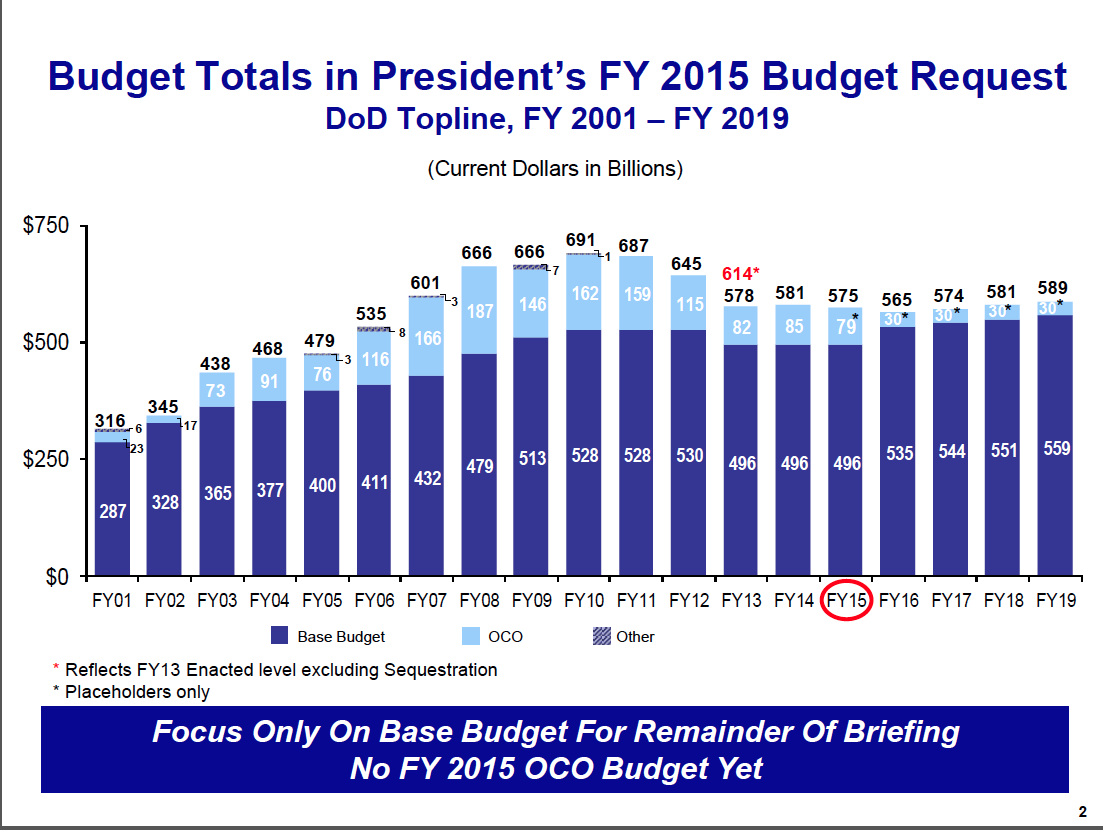

It this any way to run a railroad? No wonder nothing works right and everything the government does costs more. There’s no stability to allow for any sort of long-range plan. But you all know that. The point of all this is that through a series of improbable event, we have managed to kludge together funding to keep the US in business (such as it is). But there’s nothing in the works that I know of to fix 2016, the budget that being build right now in the Pentagon. And just like a scene out of Ground Hog Day, DoD is putting together a budget that ignores sequestration. Here’s a chart right out of the DoD 2015 Budget Briefing. Notice that there is no mention of sequestration (except to exclude it).  Now here’s a rough chart (I’m sure the numbers are off slightly) of what sequestration funding levels are relative to the DoD budget. Notice it’s $115 Billion out of round through 2019. That’s how much money the Pentagon is stuffing into the budget over sequestration spending levels.

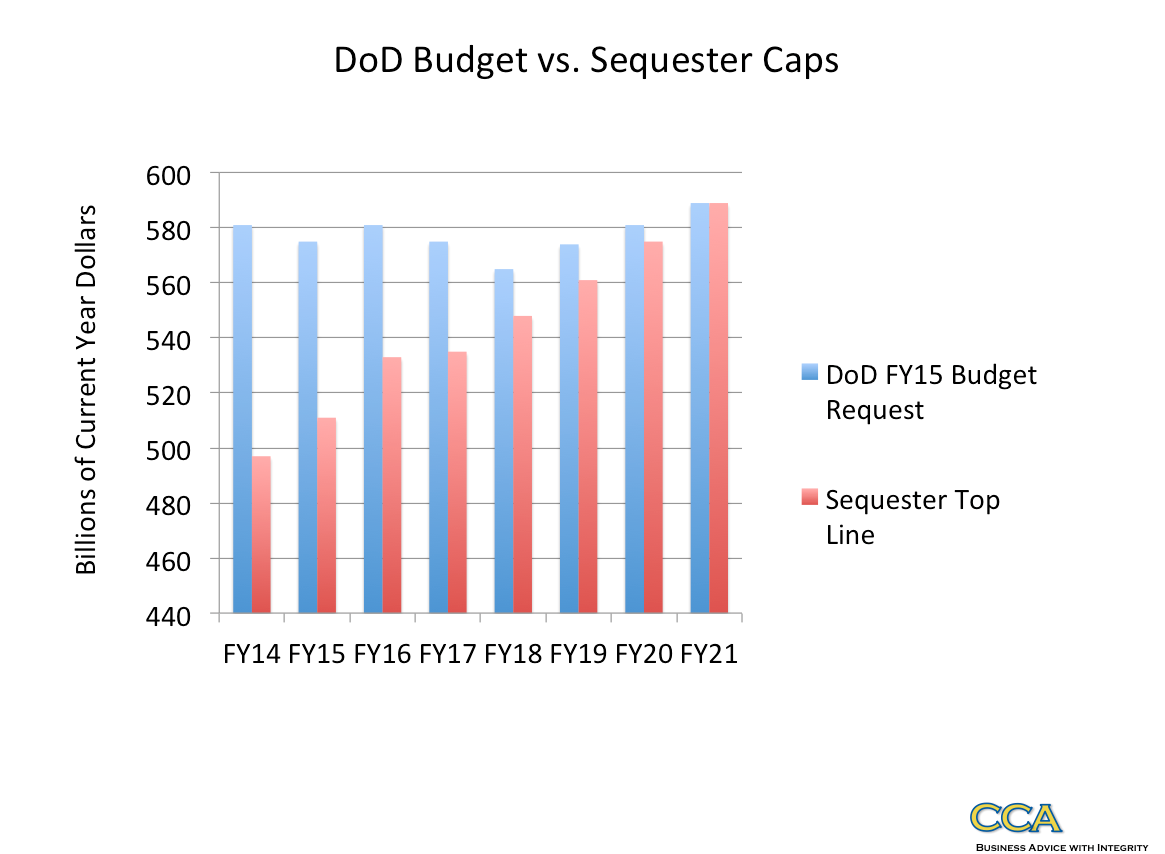

Now here’s a rough chart (I’m sure the numbers are off slightly) of what sequestration funding levels are relative to the DoD budget. Notice it’s $115 Billion out of round through 2019. That’s how much money the Pentagon is stuffing into the budget over sequestration spending levels.  The only point of this little tale is to impress upon you how important it is that we get this fixed. We can’t keep grinding our people into the dirt with endless budget drills which make no sense. There are three possible strategies to deal with the situation IMHO:

The only point of this little tale is to impress upon you how important it is that we get this fixed. We can’t keep grinding our people into the dirt with endless budget drills which make no sense. There are three possible strategies to deal with the situation IMHO:

Where do I come down?…..What the heck….let’s go for number 1. It worked last time and the politicians always fix it in the end, no matter how much pain gets inflicted in the process. And so it goes………..